At the dawn of the twentieth century, Charles Buls, the forward-thinking mayor of Brussels, employed magic lantern performances not merely to display his extensive travels but also to illuminate his socio-political ideals. These spellbinding illustrated lectures whisked audiences away to far-flung corners of the globe, deftly weaving in Buls’ passionate advocacy for cultural conservation and civic identity. His poignant recounting of the tragic Messina earthquake of 1908 not only shed light on the plight of that unfortunate city and its people but also unveiled his grand vision for Brussels. Through the lens of Buls’ magic lantern, we delve into the intricate tapestry where his globetrotting adventures and political philosophy converge, illuminating a legacy that resonates far beyond his time.

AN IMPRESSION OF BULS

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, virtual travel and the literary travelogue genre gained immense popularity. As people ventured to newly accessible destinations, they shared their experiences through emerging visual mass media, such as the magic lantern. Originally invented in the mid-seventeenth century, the magic lantern evolved into a mass medium by the mid-nineteenth century, making it perfect for virtual travel. Armchair travel became more than just an alternative to physical journeys; it emerged as a distinct pastime, leading to a boom in related consumer goods and experiences. Among the many who embraced this trend was Charles Buls.

Charles Buls (1837-1914) was the mayor of Brussels in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Dropping out at 18 after following a professional education, he embarked on study trips to France and Italy, sponsored by his father, to equip him to take over the family business as a goldsmith. On these trips, especially during his half-year stay in Italy, he not only picked up the travel germ that would remain with him his whole life, but he also developed a dual vocation.

On the one hand, he encountered the Risorgimento movement, which fought for the national unification of Italy. In Italy, he was also confronted with the social misery that the local population endured. This partly led to his ambition to go into politics and have real societal impact instead of becoming a goldsmith like his father. On the other hand, he became a firm believer in the significance of local and national culture through his museum and art gallery visits. He grew convinced of the importance of educational and scientific institutions for popular emancipation and defended the key role of preserving native languages in safeguarding the unique culture of a specific place.

Inspired by his study trip to Italy, Buls began catching up on his own educational backlog, studying German, English, Dutch, and Latin. He developed a persistent interest in art history, which included architecture and urban planning. Inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, he believed that these disciplines should develop steadily, like nature. For Buls, art and beauty needed to be functional and rational as well.

"TO CATCH THE EYE": AESTHETICS AND EDUCATION

Buls can be characterized by his two major areas of interest: aesthetics and education, as captured by this quote from newspaper Le Peuple: “Mr. Buls is known to be an artist and a tourist; he sees much and feels deeply. From each of his journeys he brings back a wealth of picturesque notes, original observations, and valuable lessons, and in his generous erudition he likes to popularize his impressions” (21 October 1902, p. 2).

As the standard-bearer of the picturesque urban planning movement in the nineteenth century, Buls sought to defend local architectural styles and histories against large-scale Haussmann-inspired replanning initiatives. He was also a traveller with a keen eye for “the picturesque”: things worthy of being painted. In his travel diaries, he painted places he visited (Fig. 2).

Buls also had a passion for popular education. His own experience had taught him that experiential and independent learning gave him more opportunities in life, a lesson he wanted to share with as many people as possible. This motivation led him to become a major promotor of scientific popularization. In keeping with contemporaneous pedagogy, he placed significant emphasis on including visuals in popular education. “To catch the eye,” in Buls’ own words, can be taken as the credo of this movement.

Lectures illustrated by magic lantern slides were ideal didactic devices to use art for social emancipation. Through the many lectures he gave, Buls embarked on a quest for the perfect visual language that could effectively convey educational messages to audiences, particularly to the uneducated, enabling them to acquire knowledge without too much effort. Buls believed that education and emancipation had to go hand in hand with civic pride and a revival of crafts and cultural traditions, fostering a strong sense of community and bustling urbanity.

A MAYOR ON THE MOVE

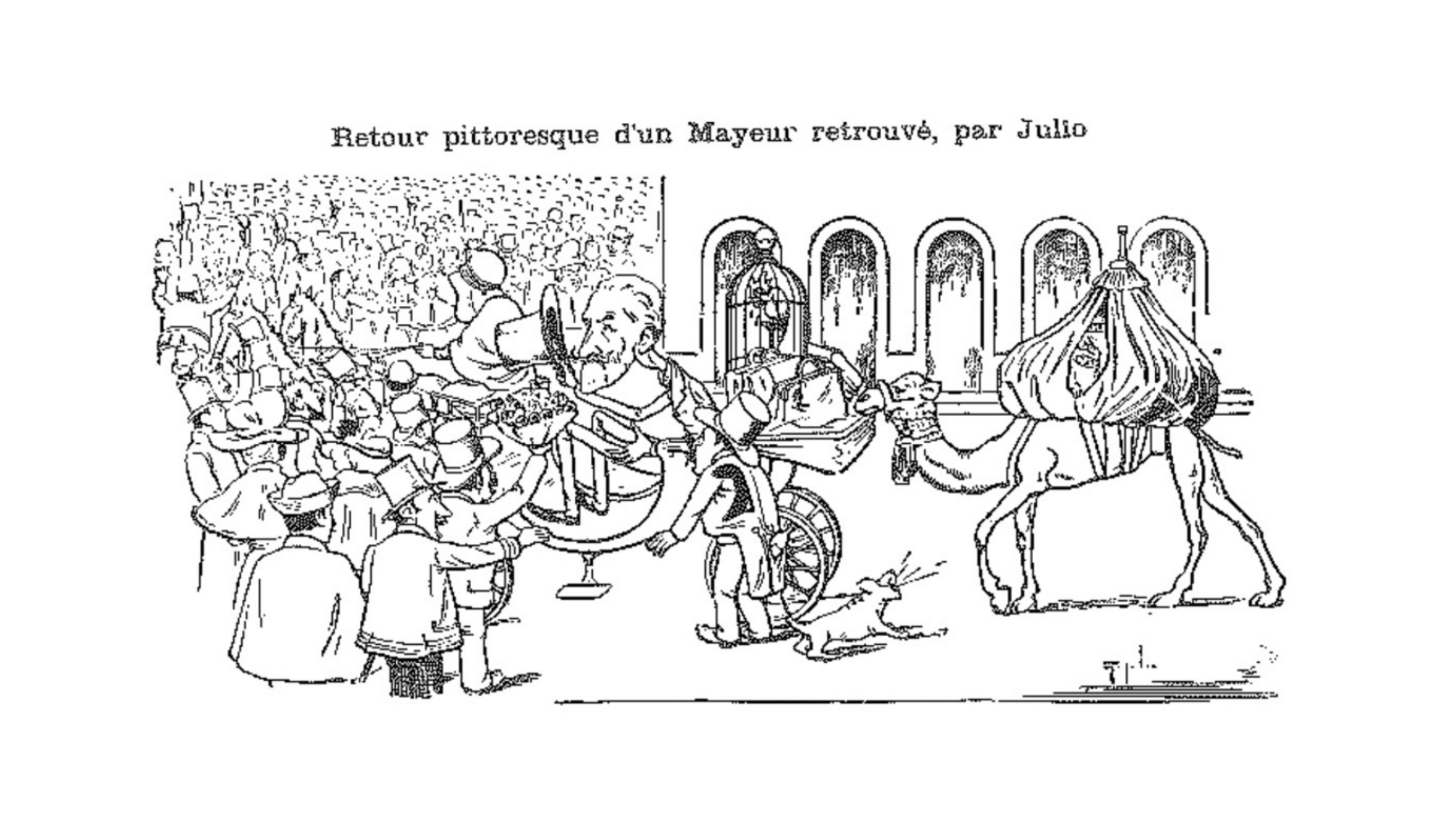

Buls was already famous for his many travels abroad during his tenure as a mayor. During his absences, he was replaced by other council members. The caricature above (Fig. 3) shows mayor Buls returning “in a picturesque manner” from one of his many travels. Even in this rather critical depiction, however, he is shown bringing back his findings, including an exotic bird and a camel or dromedary, to educate and benefit the population of Brussels as well. During his tenure, Buls was especially dedicated to safeguarding local heritage and national culture. He restored the Grand Place of Brussels, introduced bilingual street signs, and fervently supported the establishment of the Flemish theatre, the only Dutch-language theatre in Brussels at the time.

After his resignation in 1899, Buls intensified his travels, always meticulously preparing his trips and documenting his experiences. He visited diverse countries such as Norway, the US, Egypt, Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and Siam (now Thailand). Yet, he also explored places closer to home. Italy was arguably his favourite, as he visited it almost every year during Spring. Buls loved exploring Italy, especially as he occupied the position of curator of the Cabinet d’Archéologie Gréco-Romaine at the Université libre de Bruxelles. In his diary, he noted that he accepted this position because it allowed him to “travel in pleasant conditions”. Despite stepping down as mayor, Buls still had clear convictions about societal organization and wanted to keep influencing policies. Recounting and performing his travel experiences, mediated and amplified through magic lantern slides, were key in accomplishing this.

THE ATTRACTION OF THE ABYSS

Buls’ illustrated lecture on the Messina earthquake of 1908, the most destructive earthquake ever recorded in Europe, exemplified his socio-political and aesthetic philosophy. On 28 December 1908, the region of Calabria and the city of Messina were completely destroyed following a devastating earthquake. Messina lost almost half of its population and at least 91% of its structures were destroyed or irreparably damaged. Therefore, Messina is to this day often called ‘the city without memory’. The next day, the papers already reported on the disaster, dedicating their title pages entirely to the destruction. In the first months of 1909, lantern lectures about the earthquake started to emerge.

There is much to say about the concrete iconography of the lantern slides Buls showed during this particular performance (Fig. 4). The expected scenes depicted the earthquake’s profound effects on buildings and people, while more abstract slides captured the geological power of the earthquake. Buls attempted to make the impact of the disaster more tangible by situating the event in a broader historical timeline of previous disasters, reminding his audience of Pompeii’s destruction by Vesuvius. Then he delved into art history and considered the disaster from the viewpoint of previous generations. Their sweat, blood, and tears were soaked into these stones and their heritage or final voice was in grave danger of being lost forever.

Buls’ lecture contained an activist message as well. He argued passionately against haphazard modern reconstruction in favour of urban planning that honours a locale’s rich traditions, thereby preserving its historical essence. He shifted the event’s significance from the actual and the temporary to the historical and the eternal, ultimately stressing the importance of identity. Impersonal modern urban planning would destroy the last ties between the affected population and its ‘home’. Eventually, Buls’ goal was to reconstruct the bond between people and their surroundings ‘before it’s too late,’ as this bond was quickly being destroyed in the modern city.

ALL ROADS LEAD TO... BRUSSELS?

Ultimately, Buls’ message extended beyond Sicily to his beloved Brussels. The ‘modernization’ of Brussels was in full swing when Buls delivered his lecture on the Messina earthquake. The neoclassicist projects championed by Leopold II had partly led to Buls’ resignation in 1899. Although Buls was an avid lover of travel and culture, and had a penchant for Italian art specifically, he did not accept neoclassicist influences in Brussels, as the city had its own rich architectural history.

Instead, Buls especially supported art movements inspired by the local Flemish past, like the neo-Flemish renaissance movement (Fig. 5). He argued that Brussels should reconnect with its own cultural past, art historical backgrounds, and traditions that are tied to actual locations and people, rather than the worn-out classical canons (Fig. 6). Buls urged his contemporaries to discover and further build on the inherent values within their historical cities and resurrect history in order to keep the people connected to their heritage and to safeguard the thread that connects the present and the past.

Author

-

Eleonora Paklons is a doctoral researcher on the Bias in History project at the University of Antwerp. Her research focuses on representations of places in magic lantern slides (1880-1929), ranging from the Roman Forum to the pits of hell.